"The primary purpose of the Museum is to help people enjoy, understand and use the art of our time." Alfred H. Barr Jr.'s diagram is familiar, or at least associated, with a significant proportion of the world's people. At first glance, one sees a tangle of arrows, intricate names, and dates. What should we know about the scheme in question and the creator himself?

The more carefully we look at the diagram in question, the more clearly we see the essential elements, the familiar buzzwords. One could say that these are a kind of jigsaw puzzle, thanks to which we will understand, in the final result - our image - the art of the 20th century. But are we sure?

Poster and book cover of an exhibition "Cubism and Abstract Art" in MoMa in 1936 (source: www.pinterest.com)

Barr's mind map was created for the Cubism and Abstract Art exhibition of 1936 and, in fact, is still somewhat controversial today. Who exactly was Mr Barr?

A shy scholar, an inspired showman with a reputation for being difficult. He was extremely critical when things did not go his way. Many called him the 'Pope of Modernity' and his palace was a museum. He was an American art historian and the first director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. He came to live and work in an extremely dynamic period of the 20th century. Not only that, but he used modernism to legitimize modern art. Furthermore, he believed in an aesthetic based on the intrinsic qualities of a work of art, the materials and techniques needed to produce them - a truly formalist approach. This was helped by his numerous trips to Europe, during which he met the most prominent representatives of the avant-garde. All this helped to put one of the world's most famous museums of the time on a pedestal.

The museum opened on 9 November 1929 on the initiative and foundation of three exceptional women, Abby Rockefeller, Lillie Bliss and Mary Sullivan. The first exhibition featured works of European art: van Gogh, Gauguin, Cézanne, and it was a real hit. More than 50,000 people visited the exhibition in five weeks. In the same year, he met his future wife, Margaret Scolari. Despite everything, his path has not been easy. He was repeatedly accused of leaning too much towards the avant-garde and sometimes of being too small. Barr was often accused of favouring abstractions and rejecting figurative art, and vice versa. However, this never discouraged him from sticking to his task, for which he was appreciated by his colleagues.

He looked at art comprehensively and was interested in all areas. He wanted to show the New York world the best of modern architecture, posters, chairs, and films, and attack the complacency with which our successful designers considered their 'modernist' skyscrapers and refrigerators, gothic dormitories, pompous super films, banal billboards and cynical promotion about 'artificial ageing'. Thus, in 1935, new fields became part of the museum's programme.

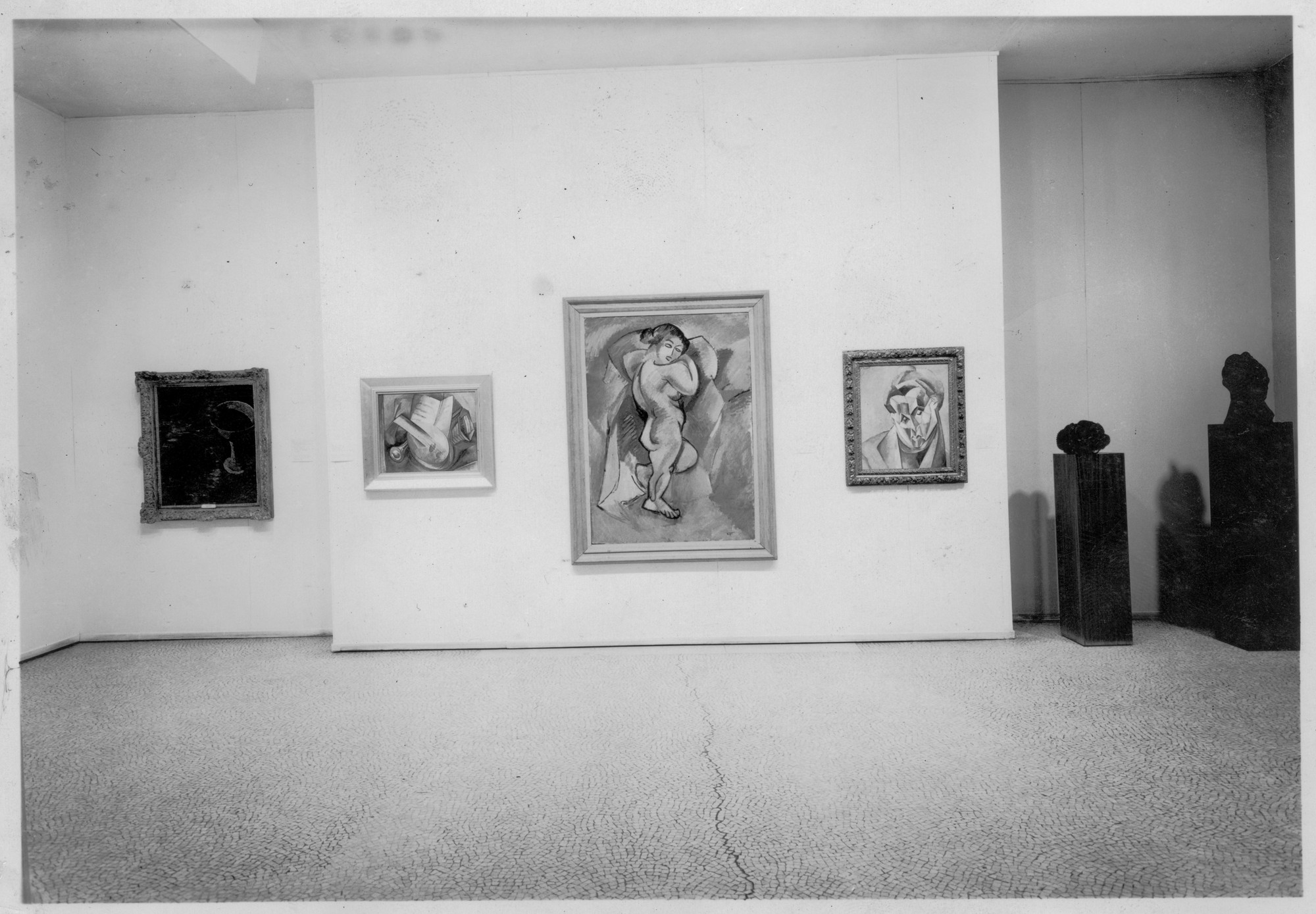

One of its most pioneering exhibitions was the one in 1936 on Cubism and abstract art. Cubism became the first impetus for the story written by Barr. His famous diagram confirms this. It was a link between 19th-century art and more recent trends. Thanks to Barr's efforts, the museum has created a magnificent collection of Picasso's works, at the heart of which is 'Les Demoiselles d'Avignon' (1907), a painting that symbolises the birth of Cubism.

The exhibition illustrated the genealogy of modern art from Cézann and Gauguin to the Bauhaus and other modern trends and tendencies. This is how the famous map was created, which Alfred H. Barr worked on for more than a decade before it was included in the exhibition catalogue (and also became its cover). The aim of the exhibition was to organize the collected material in as practical and accessible a way as possible. As I mentioned earlier, mainly European acquisitions were shown, but there were also a few American artists who, in the opinion of the art historian, made significant contributions to abstract art.

Some truly great names can be mentioned here, about whom young art students, and not only, are learning and reading: Alexander Archipenko, Hans Arp, Umberto Boccioni, Constantin Brancusi, Alexander Calder, Paul Cezanne, Giorgio de Chirico, Theo van Doesburg, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Naum Gabo, Alberto Giacometti, Paul Gauguin, Juan Gris, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Le Corbusier, Fernand Leger, El Lissitzky, Kazimir Malevich, Henri Matisse, Piet Mondrian, Henry Moore, Francis Picabia, Pablo Picasso, Gino Severini and many others. I think that any curator putting together an exhibition would rub their hands gladly at the thought of going to work with such works. They are all part of the history of countries or the world in general. The curator knew he had good taste, which is why the museum's collection is also his private one.

The question of abstract art has always been contentious, including among artists. Some, such as Matisse or H. Kahnweiler, argued that it was not in keeping with our Western spirit and did not reach beauty, lacking action, but others were open to it, seeing complete creative freedom liberated from the world of taste and consumption. An interesting position was raised by Picasso, who believed that there was really no abstract art, because the idea of the object would stay with people forever. There is no painting without figures even if it is only a square or a circle because these are symbols only perhaps further from our emotions, and still, Theo van Doesburg believed that nothing is more literal than line, colour and plane.

Exhibition "Cubism and Abstract Art" 1936 at MoMA's (source: www.moma.org)

By the mid-1930s, this argument had already faded somewhat. "Abstract art today does not need defending. It has become one of many ways of painting, sculpting or modelling. But it is still not the kind of art that people like without a bit of learning and sacrificing prejudice. It is based on the idea that a work of art, such as a painting, is worth looking at in the first place because it represents the composition or organization of colour, line, light and shadow. A resemblance to natural objects, though not necessarily!" - he wrote in the introduction to the exhibition catalogue. When Barr created the exhibition, he did not know that it would be the 1960s that would be the golden age for abstract art, but to some extent, he had built up its ground thirty years earlier.

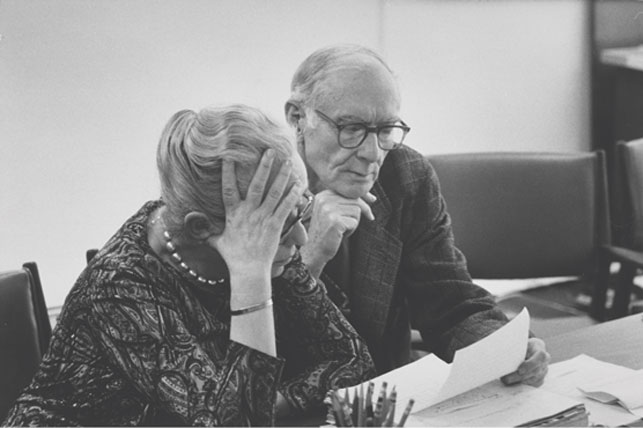

Left to right: Alfred H. Barr Jr., Picasso, Jacqueline Roque and Margaret Scolari at Picasso's home, 1956 (source: www.moma.org)

Words are insufficient to define the essence of modern art. Any attempt further complicates this task (indeed, the definition of the word 'beauty' faces similar problems). But perhaps this is the key to the success that abstract art has had and continues to have. The definition can destroy it, pigeonhole it, and its greatest asset is its freedom. The artist is not constrained by anything, he gives himself over to a passion, to an idea.

Often Barr's projects were extremely bold, even crazy. Perhaps for this reason, too, he was dismissed as director in 1943, although there were certainly many factors. Nevertheless, he won the affection of the staff to the extent that they always sought advice from him on museum matters. His message was a rational approach to modern art, as he used to say, 'without hysteria or prejudice'. He was the creator not only of this but of many other exhibitions that brought fame to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Despite a very active lifestyle, he suffered from Alzheimer's disease. He died in 1981.

Alfred H. Barr Jr. with wife Margaret Scolari (source: www.moma.org)